Pronouns aren't Gender: A nerdy post about pronouns, grammar, languages, and gender

This is not about singular they

In English, we currently use pronouns to talk indirectly about gender identity. I don’t know how this started, but it clicked with me when I first heard about it. Using pronouns to talk about gender identity is possible because English assigns gender to third-person singular pronouns (she, he) but not to other pronouns (I/me, you, it, we/us, they/them, etc.).

After a few years of sharing pronouns as a stand-in for sharing gender identity, some anti-trans people have now confused “pronouns” with “transgender identity.” I’ve heard statements like “I don’t have pronouns” or “I won’t date a woman with pronouns.” Smack my head.

Come on! Didn’t anyone pay attention in English class? On top of the pain from transphobia, the neurodivergent grammar nerd and language-lover in me is suffering.

This is my lecture about how pronouns and gender identity are not the same thing or even necessarily intertwined.

The term “gender” was borrowed from grammar. It has been used to refer to humans only since the 1950s and 1960s. “Gender” was useful in the women’s rights movement because it provided language to separate roles, expectations, and social-cultural aspects of differences between women and men (gender) from biological differences between females and males (sex). It allowed (White) women to argue that staying at home and attending to domestic duties was not The Immutable Role of Women, but sociocultural, and therefore changeable. Powerful stuff.

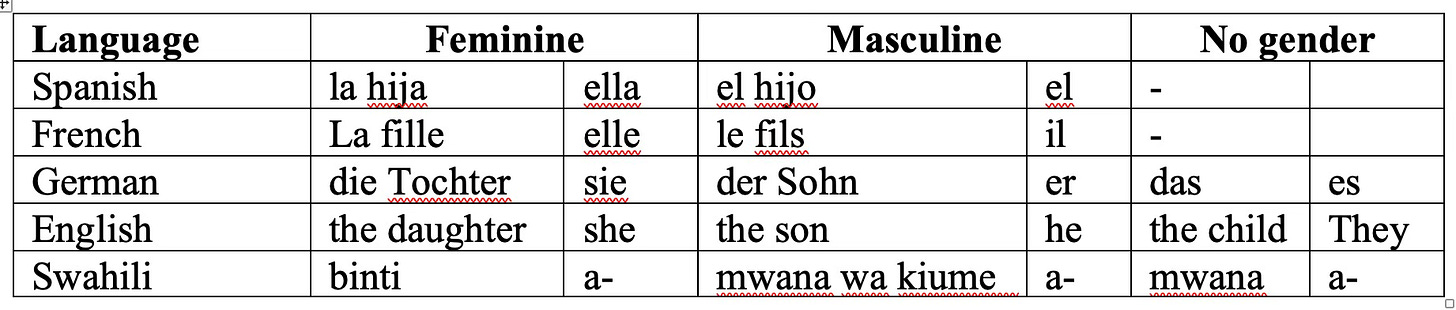

But let’s talk languages. Gender in grammar differs between languages—some have more gender and some have less. Anyone who speaks Spanish or French, for example, knows that nouns have a feminine or masculine grammatical gender assigned to them. German also has a neuter/neutral gender. The gender of nouns influences the articles (the, a, those, etc.), adjectives, and pronouns connected to those nouns (la chaise bleue vs le sac bleu). In many other languages, the third person plural (they/them) is also gendered. In French, ils refers to a group of men or a mixed-gender group, and elles refers to a group of women. (See how patriarchy is built into language?)

Arabic also genders “you,” so it’s a different “you” pronoun when speaking to a man, a woman, 2 men, 2 women, 3+ men, or 3+ women. Swedish has a third-person singular gender-neutral pronoun for humans: han (he), hon (she), and hen (they, singular). Hen is used when you don’t know a person’s gender, much like the singular they in English, so it’s been adopted to refer to nonbinary people (without anyone saying, “BuT tHaT’s gRamMatiCalLy iNcorREcT!” [It’s not incorrect in English either.])

In other languages such as Swahili (and other Bantu languages and many other language families), grammar is not organized around gender at all. Instead, there is a complicated system with noun classes. The noun classes determine the adjectives, pronouns, articles, etc. There’s only one word for he/she, but over a dozen ways to say it, its, they/them, this, that, and those, depending on if it’s a chair, a car, a tree, or a human or animal, etc. That means that pronouns do not indicate gender. Asking “What are your pronouns?” makes no sense in those languages.

The languages we speak influence how we think about the world. It’s hard to think about a concept if there’s no word for it. I had no word for “transgender” when I was young, so I could not organize my many thoughts and experiences about gender into a cohesive whole.

I believe that speaking multiple languages helps us see the world in more expansive, malleable ways. If one thing can be a table, Tisch, or meza, maybe it’s easier to see things from others’ perspectives, develop more empathy, or be more creative. What else can we imagine?

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations—you’re a language nerd like me. I have formally studied English, Swahili, German, French, Arabic, Afrikaans, and American Sign Language, but do not claim to speak them all.

I love it when you need out about languages. Great work.

This was a fascinating read, thank you for writing it.