A new study, titled “Legal gender recognition and the health of transgender and gender-diverse people: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” was published in early May in Social Science & Medicine.1 (I’m one of the authors!)

In my series on gender transition, I covered legal transition as one of four categories of transition options: psychological, social, legal, and medical (hormonal and surgical).

Legal transition involves steps to legalize your transgender/nonbinary identity. This typically involves legally changing your name and/or gender marker (i.e., the legally recognized sex or gender). These processes are full of hurdles—time, money, legal restrictions, and transphobia. These prevent a lot of trans/nonbinary people from being able to transition legally. Ever.

To first understand the basics of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, I’ve written a primer to assist you in evaluating what you read.

tl;dr: Legal gender recognition is good for health

In short, the review shows that legal transition is good for health.

Specifically,

Living in a place with favorable laws and policies that allow trans and nonbinary people to change their gender marker and name on official identification documents is good for trans people’s mental and physical health.

Having ID documents with affirmed gender identity and name is good for trans and nonbinary people’s mental health.

Background

Last year, I worked on a project looking at all the global evidence on these issues. My role was to carefully and systematically grade all the evidence for its quality and rigor. I pulled all the numbers. I created graphs and charts with a stupid amount of footnotes. And it’s finally published!

The World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned this study to systematically identify, review, and evaluate the evidence available worldwide. This is one step in a lengthy and complicated process to develop its first guidelines on trans/nonbinary health2 This review was one of several reviews, all with different topics within trans health.

Results

What did the study find?!? Well, since we included seven categories of outcomes, we have a lot of findings! (See Notes on Methods, below.)

Legal gender recognition was associated with these Outcomes:

Quality of life

Higher life satisfaction scores

Mortality and life expectancy

No studies on this

Mental health, including substance use

25% less suicidal ideation, but further analysis showed that discrimination and psychological distress likely accounted for some of the suicidal ideation, and not legal transition alone

Less suicidal planning, and it was statistically significant, meaning the results are unlikely to be due to chance

29% fewer suicidal attempts, but the uncertainty was high, i.e., the results were not statistically significant, meaning the results might be due to chance, or the small number of attempts meant there may or may not be an association there, but this data couldn’t show it, etc.

Less psychological distress, and it was statistically significant, meaning the results are unlikely to be due to chance

Non-suicidal self-injury couldn’t be said either way with the available data

Depressive symptoms couldn’t be said either way with the available data, but the trend points to reductions

36% less tobacco use, but the uncertainty was high

Access and utilization of health services

Studies were too different to combine results, but three studies indicated increased access to gender-affirming care or general healthcare.

Stigma, discrimination, and violence

The studies were too diverse to be combined into a single result. Disparate outcomes included anticipated stigma, legal policy scores, healthcare discrimination, gender identity concealment in healthcare, and fear of mistreatment in public. See Values & Preferences, below.

Physical health

Fewer sterilization surgeries. The two studies were too diverse to combine their results, one about HIV and one about gonadectomy. The latter showed that in the Netherlands, the requirement to undergo gonadectomy (removal of testes or ovaries, aka sterilization) was a barrier to people legally transitioning. Once the country removed that requirement, more people kept their gonads, especially transmasculine people.

Socioeconomic status

More income, employment, and housing security, and these were statistically significant.

Values & Preferences

In addition to reviewing statistics, my colleagues also examined 31 studies identified through the systematic review that reported trans/nonbinary people’s values and preferences around legal transition.

People reported that not having the correct ID meant privacy violations and being “outed” by the ID

They also worried about that happening (“anticipated discrimination”)

So they avoided some situations, including healthcare

Trans/nonbinary people felt like less discrimination happened around IDs if they had the correct ones

Safety was a priority when making decisions about changing IDs

People wanted options: female, male, nonbinary (or third gender)

People worried X markers would increase stigma and discrimination3

People wanted gender markers removed from IDs altogether to avoid all this

People wanted governments to stop requiring diagnosis, medical intervention, and/or sterilization for legal transition, as these were pathologizing, demeaning, and costly barriers

In Argentina, trans women felt that the positive gender identity laws promoted visibility, advocacy, and civic engagement, and helped with access to education and formal employment.

Conclusions

We concluded that although there are gaps in the evidence and there’s always room for more research, there is enough evidence to recommend allowing legal gender marker/name changes for trans/nonbinary people.

Into the Weeds: Methods

For those of you who want more of a deep dive, read on.

The authors and I followed strict systematic review guidelines, called PRISMA, and registered the protocol for the review with PROSPERO. These help ensure rigor and quality according to accepted standards.

PICO

To define which studies would be eligible to include in the review, my colleagues first defined PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes). In this case, we had two interventions, two comparators, and seven outcomes.

Population: transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse people, meaning anyone whose “gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth.”

Intervention/Exposure 1: laws, policies, and/or administrative procedures aimed at providing legal gender recognition and following international human rights standards

vs. Comparator 1: lack of such laws, policies, or noncompliance with international human rights standards

Intervention/Exposure 2: Having an official ID that matches current gender identity (gender and/or name)

vs. Comparator 2: lack of such ID

Outcomes:

quality of life

mortality and life expectancy

mental health, including substance use

access and utilization of health services

stigma, discrimination, and violence

physical health

socioeconomic status

Refer to my primer on systematic reviews for more detailed information on the methods, including defining the search terms, title & abstract screening, and full-text review.

Notes on Study Design, Association, Correlation, Causation

Note that almost all the 24 studies were cross-sectional designs, meaning the exposure (e.g., legal transition) was measured at the same time point as the outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms). This means we cannot determine which one causes the other. We can only say they are associated or correlated, as in, we tend to find A & B together, but we can’t say if A causes B, B causes A, or it’s something else (C) causing both of them. Because of that, epidemiology considers cross-sectional designs to be weaker evidence generally. (But it’s also the cheapest and easiest, so it’s done a lot. Trade-offs.)

One of the studies was serial cross-sectional, meaning data were collected at multiple time points, but not from the exact same people. This is better than a single cross-sectional study, but we still can’t determine cause, just trends and associations. Think of political polls throughout an 18-month campaign. Each time the pollsters collect their data, it’s different people, but about the same candidate, and we can see changes in favorability fluctuate over time.

One of the studies was a cohort study. A lot of the evidence we have on gender-affirming care (especially for minors) is from cohort studies. We just don’t have many legal transition cohort studies. Cohort studies collect data from the same people at multiple time points. This can be prospective (e.g., starting now and following people into the future) or retrospective (looking at clinical records from two years ago to the present). These are also called longitudinal cohorts.

Stay tuned for more about study designs and their strengths and weaknesses; the anti-trans folks use study design to argue that we don’t have solid evidence for gender-affirming care. They are wrong.

Data Abstraction

Once we identified the 24 studies that fit the eligibility criteria (from the 2,748 gathered in the search), three of us abstracted (or extracted) the relevant data from each of the studies.

We used Covidence, a software designed for systematic reviews, to extract relevant information into a template. This ensures we have the same categories of information for all the included studies (see the manuscript for more info). We did this in duplicate, meaning two people pulled the data for each study and then compared them. After all, we all make mistakes, such as mistyping something, transposing numbers, or misreading information. Again, this doubled work is for rigor and quality.

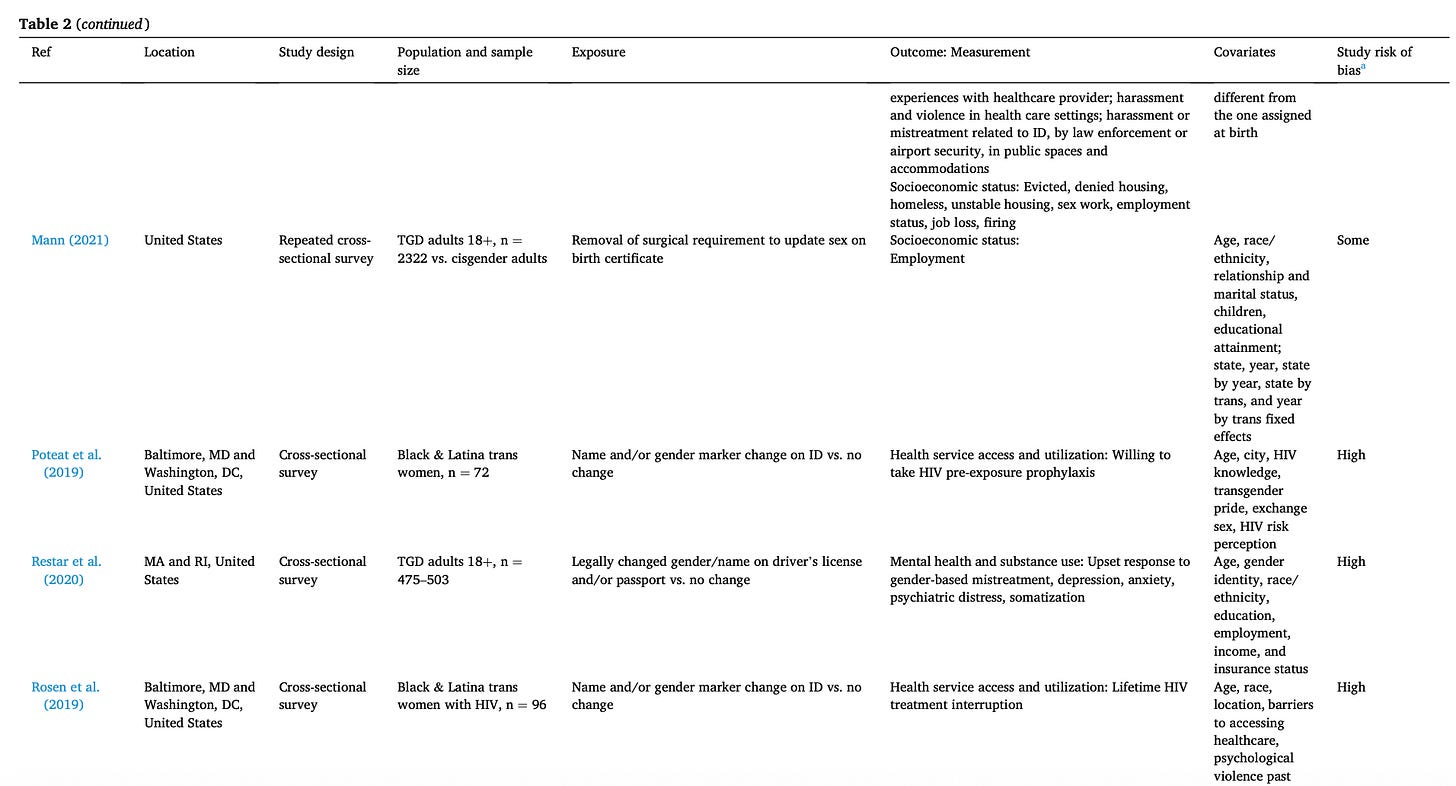

Table 2 contains most of this information. This helps readers see exactly what went into the review and meta-analysis. Here’s a slice of that table:

Risk of Bias

We also had to evaluate the quality of each of the included studies. For this, we used standardized tools to rate each study. Since studies have different study designs (randomized controlled trials, non-randomized intervention studies, and non-randomized exposure studies), we used different tools for each one. At least two people (including me) on the team did this for each study. If we disagreed, we discussed it, and a third person determined the final decision.

GRADE

Beyond risk of bias for each study, we also evaluated the body of evidence as a whole for each outcome. This was my primary role in the project. I used WHO’s GRADE tool and online software to create tables for each outcome. For example, for the physical health outcome, we found studies about HIV and tobacco use. For the mental health outcome, we had several suicide outcomes (thinking about it, planning it, attempting it), psychological distress, non-suicidal self-injury, etc.

Then I looked at all the evidence we have on that particular outcome, say psychological distress, the quality of the studies going into it, how consistent the findings are, etc. (The categories are study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.) Beyond that, the WHO takes into account values, preferences, human rights, and practical considerations. So the available data alone are not enough to inform their guidelines.

It involved a whole lot of numbers, spreadsheets, forest plots, data analysis, coding, and checking and re-checking. I reworked entire tables after feedback from a GRADE methods expert. Twice. It involved lots of size 9 font and dozens of footnotes. It took many months.

Meta-Analysis

For any specific outcomes where we had at least two studies with quantitative results, my colleague conducted meta-analyses. For example, three studies provided statistics (odds ratios) on past-year suicidal ideation, and four studies provided statistics on past-year suicide attempts. Had a study provided “lifetime suicidal ideation,” we did not combine that with “past-year suicidal ideation” because the time frames are vastly different. These analyses are presented in the manuscript as figures. I explain more about how to interpret them in my primer.

Social Science & Medicine is a well-respected journal that integrates sociology, anthropology, and other social sciences with biomedical sciences such as public health. My graduate studies fell within that overlap, and it was a journal to which I aspired to be published.

Most of the world follows WHO recommendations, partly because individual countries don’t have the capacity to develop their own guidelines. The US generally relied on the CDC for guidelines, but in 2025, it was partly defunded and no longer issues infectious disease warnings.

We are seeing this play out in the US in 2025, with the federal government not recognizing X gender markers as well as requiring sex assigned at birth to be on federal ID, i.e., passports

I would like to have the X option, but having the field gone would still be better than always seeing it misgender me.

💜🏳️⚧️💙 Thank you very much for conducting and sharing your research. I live in a state where the only 2 gender markers allowed on any state documents are M / F. As a non-binary adult, this a frequent source of frustration because it is a cruel and intentional form of institutional gaslighting.