When my son was a teenager, I transitioned from his mom to his dad.

Growing up, I was a tomboy, but in a Mormon family in Utah, so “exploring my identity” meant shoving myself into the mold my parents modeled: stay-at-home-mom with seven kids, standing dutifully by my husband. I did begin that journey; I married a Mormon man when I was 19 and gave birth when I was 22—the age my son is now. For this essay, I’ll call him Ben.

When Ben was two, his dad and I left the Mormon faith. We began the potty-training journey and the official exodus from the church on the same weekend by making a family trip to buy “big boy underwear” for all three of us. (That was 20 years ago this weekend.) Over the following weeks, my son switched between his SpongeBob underwear and pull-ups, and I swapped my Mormon underwear for the least girly boy shorts I could find. (That I preferred to call them big boy underwear for myself should have been a clue, but alas.)

Fast-forward to the summer my son turned 15. My little family and I had been living in rural Tanzania since Ben was 9. As is customary in many cultures across sub-Saharan Africa, parents can be called by the name of their oldest child (or oldest son). It’s respectful, somewhat like using Mr/Miss/Mrs/Mx in English. So most people called me Mama Ben and his other dad Baba Ben.1

Ben had spent a few weeks visiting family and friends in the US and Europe and had just flown home to Tanzania. I had spent the past year quietly exploring my gender identity. Instead of going all the way home in Southern Tanzania, Ben, Baba Ben, and I traveled by airplane, car, and motor boat to arrive at Gombe Stream National Park. This verdant, mountainous area is where Jane Goodall (my childhood idol) studied chimpanzees. It had been a dream of mine to visit and trek for chimps in the forest.

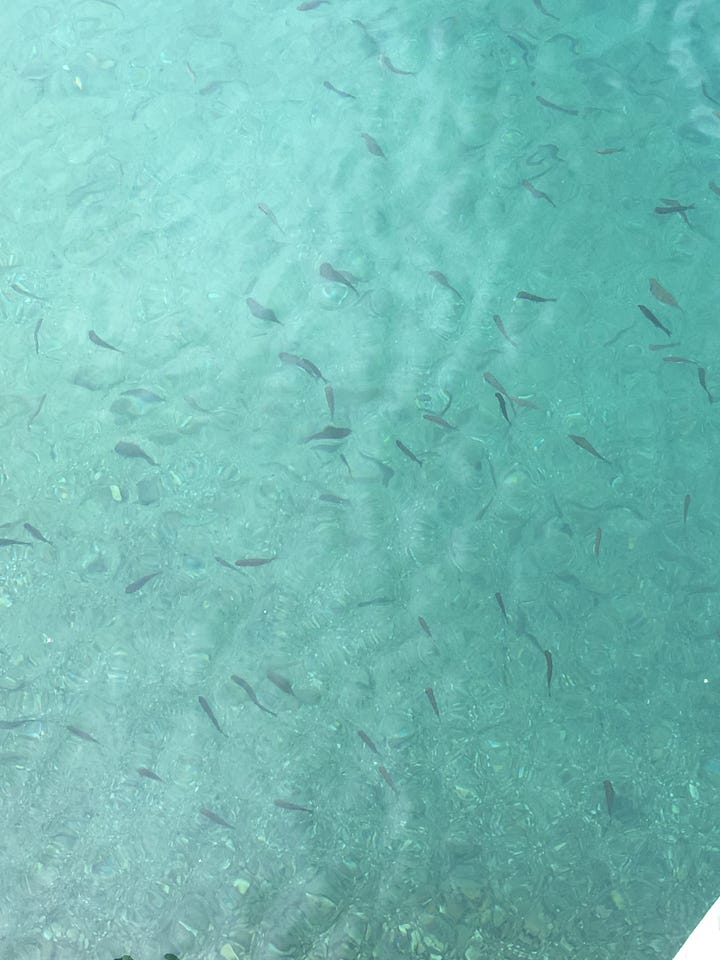

The day had been amazing; with a guide, our little group happened across a troop of chimps right on the path. We then followed them partway back to camp. After lunch, Ben and I sat on the steps outside the roadhouse, catching up. A giant mango tree provided shade. We watched baboons crash through the trees up the hill and climb onto the roadhouse balcony, looking for scraps. The gentle waves of Lake Tanganyika lapped a few yards away, and vervet monkeys played nearby. A baby monkey hopped down a couple of steps toward us before realizing we were there. It stopped so close I could have reached out to touch it.

Sitting there at Gombe, apropos of nothing, Ben came out to me as straight. I was proud of him and myself. Not for being straight—I had hoped he’d be gay, actually—but because it meant I’d raised him to be LGBTQ-friendly. Straight was not the default in my house.

Since we were on the subject, I decided it was a good time for me to come out to him. At the time, nonbinary felt like the right label for me, and I’d told his dad a few weeks before.

I said to Ben, “Hey, bud, I’ve got something important to tell you.”

He interrupted me to say, “No. Don’t say it. I know what you’re going to say. Don’t say it.”

I was baffled. Yes, I had been dropping hints, like applauding his prospective boarding school2 because it accommodated nonbinary students. But I did not expect this reaction.

“Dude, this is important to me,” I said, “I’m nonbinary.” I was hurt.

His face hardened and he said, “I don’t believe you.”

“What do you mean you don’t believe me? What if I had said to you that I didn’t believe you are straight?”

He said, “I wouldn’t care, because I know I’m straight” with the kind of attitude only teenagers can manage.

I felt myself getting upset, so I asked to talk about it more later, and stepped away. After a couple of hours at the beach, we reconvened. This time, I told him some of the things that made me feel I’m not a woman, like declaring “I’m going to be a boy when I grow up” when I was three. I thought I’d grow up like dad, and I never felt comfortable in women-only spaces. And a thousand other things I have felt throughout my life.

Dropping the label “woman” was liberating for me. Not because I didn’t want to be a woman. Not because there’s anything wrong with being a woman. But because I’m just not one.

After a few of my stories, he said, “Oh. I didn’t know all that about you. Okay, cool. What pronouns do you want me to use for you?”

My heart swelled; I tear up at the memory.

Aside for animal-lovers: The next day, we trekked more and followed a chimp mom-baby pair for about 30 minutes. The baby played while the mom napped; she would reach up and pull the baby down out of trouble every few minutes. Later, the baby nursed. Then the mom created a tool to fish for termites, and the baby tried to copy her. This was the exact behavior that Jane Goodall had seen, which revolutionized how we think about non-human animals.

As the months went by, I wasn’t quite settled with the nonbinary label. I continued in therapy, journaled, and inhaled trans memoirs. Six months after coming out to Ben, the last of the gender denial fell away, and I admitted to myself, “I’m a guy.”

One book I found incredibly helpful during my exploration was Dara Hoffman Fox’s You and Your Gender Identity. Everyone—cisgender people, too—could benefit from exploring gender.

Ben was the first person I told. He said, “You say you’re a guy, you’re a guy.” Like any teenager, he was most worried about whether this might interrupt his IGCSE3 school finals. I promised to keep things under wraps for a few months, but I did tell his dad. We divorced a year later—that’s another story.

As I slowly grew into my true gender identity, I began to ponder what this meant for me as Mama Ben—Ben’s mom. At one point, I asked him if we could find an alternative for “Mom,” because Mom felt very gendered to me.

He said, “But you are my mom. It’s not gendered to me. You’re just Mom.”

I said, “Okay,” and dropped it. This was a transition for both of us, after all. As he went through his late teenage years, we had some rough patches, like many parent/teenager pairs do, and the pandemic hit during his senior year—it was hard on him and on our relationship.

After a year or so, Ben revealed that during his junior year at the boarding school, he had been upset with me. He thought that he was losing his mom. But when I kept showing up for him, he realized I was the same person, and I loved him as fiercely. I just have a different look now. And I’m happier and better adjusted, which means I can be a better parent.

Ben also said that he felt some guilt because he feared that his existence as the child I birthed reminded me that I didn’t always have a man’s body. He assumed I felt bad that my body had done “woman” things. I can see his logic.

But that’s not how I feel. I’m so grateful that I lived as a woman for 39 years before transitioning to live as a man. I believe I am a better man for it. I am proud to be a man who has given birth and breastfed (for over a year!). Those things did not make me feel gender dysphoria; those were actually the only times before transition when I felt really connected to my body. I realize not every trans person feels similarly, but I also know I’m not alone in how I feel.

That is true for me, and it is true that removing my breasts and taking testosterone were lifesaving for me. I love that I am a man who has experienced motherhood and all the connections and complexity it brings.

Life is beautifully, wonderfully not binary.

It's been almost eight years since Ben and I came out to each other under the mango tree. Since then, he has dated a couple of nonbinary people and identifies as “not straight.”

And I’ve told him he can call me mom—as long as we’re not in a men’s bathroom.

He calls me Dad now. But I’ll always cherish being Mama Ben.

Yes, there is a stigma against people who do not have children.

In the small town I lived in in rural Tanzania, the small international school stopped after 10th grade. For Ben to finish high school, boarding was his best option.

His international school used the Cambridge (UK) curriculum. At the end of year 11 (grade 10 in the US system), students take the International or regular GCSE exams, after which they can stop school. Depending on their exam results, they can enter programs to learn trades or other skills, or go on to two more years of advanced school in preparation for university.

This is such a gorgeous essay and exploration of your feelings. When I was first coming out as trans a few years ago, I struggled greatly for lack of finding other people like me--dads who had given birth to their kids, late-in-life transitions--and it was nearly impossible to find anyone at all. There's still so much erasure around the first 43 years of my life now that I'm seen as a man, and I don't know how to reconcile that, but I have no regrets either for being who I am now or for being what I was then.

This is beautiful thank you. As a non-binary parent it’s fantastic to read such a story that resonates so hard. I’ve stuck with “mum” because I don’t feel it genders me in any way and although I had a strong disassociation with being pregnant and having a baby I have loved every second of being a mum.

My son is always the fiercest protector of my they / them pronouns. His generation gives me hope. When I shared my gender identity with him (he was about 11-12) he said “sure what’s for tea?”) #priorities